- Have any questions?

- 02 7200 2179

- media@commsroom.co

- Have any questions?

- 02 7200 2179

- media@commsroom.co

Carl Sagan said that in order to understand the present, it’s necessary to know the past. Nowhere does this apply with greater force than to the Australian media and its place in the nation’s power structure.

Media Monsters, Sally Young’s second volume on the history of the Australian media, is indispensable for anyone interested in the dynamics that drive Australian politics.

It builds on the foundations laid in her magisterial first volume, Paper Emperors, and matches it for breadth, depth and insight, synthesising ownership patterns, political manipulation and vested interests that have helped shape Australian democracy.

Review: Media Monsters: The transformation of Australia’s newspaper empires – Sally Young (UNSW Press)

Not only are these forces largely hidden from public view, but they have survived epochal social, political and technological change more or less intact. The patterns that emerged in the 19th and early 20th centuries – the dynasties, the allegiances, the political partisanship, the harnessing of journalism to promote proprietorial preferences – were still present into the 1970s. Some survive to this day: notably, the journalistic practices of the Murdoch dynasty.

Media Monsters picks up the story in 1941, where Paper Emperors left off. It covers the long period of conservative political hegemony through the 1950s and 1960s, and ends in 1972, when Australian politics took an historic turn with the election of the Whitlam Labor government.

When the story opens, it is wartime and Robert Menzies’ ill-named United Australia Party has rebelled against him, causing him to resign as prime minister. Australia’s newspapers are approaching the zenith of their reach: on a per capita basis, they will never sell more printed copies than they do in the mid-1940s.

In the period 1941 to 1946, when Australia’s population was 7.5 million, more than 2.6 million copies were sold each day. Readership was two to three times higher than that: copies were shared among family members and co-workers.

In the post-war period, a wave of industrial disputes and the challenge presented by communism had the media proprietors and their business allies in despair at the disorderly state of conservative politics.

The United Australia Party had been trounced at the 1943 election, despite nearly every metropolitan daily newspaper in the country advocating for it. In the aftermath of the party’s loss, Menzies was re-elected leader. However, he made it a condition of accepting the leadership that he had the right to form a new party.

A preliminary to this was the creation of a new conservative lobby group, the Institute of Public Affairs (IPA). It’s still with us today, in a much attenuated form, but then it was backed by what the Melbourne Herald called “a group of leading Melbourne businessmen”.

This was clearly code for an entity called Collins House. The Collins House group was a collection of companies connected by networks of powerful business figures who dominated mining and manufacturing. Among its associated companies and brands were Carlton and United Breweries, Dunlop rubber and Dulux paints. Collins House also had deep roots in the banks that were to become the ANZ, NAB and Westpac.

When Keith Murdoch became managing director of the Herald and Weekly Times (HWT) newspaper group in 1928 he became an influential figure in Collins House and a vital connection for it to the most senior level of politics. As recounted in Paper Emperors, he claimed credit for installing Joseph Lyons as prime minister in 1931. “I put him in,” he was reported as boasting, “and I’ll put him out.”

Thus Collins House drew together the entwined interests of business, mining, media and politics. It was the beating heart of power in Australian political and commercial life. Collins House fingerprints were all over the freshly minted IPA, and the new body saw to it that there was a newspaper director on its inaugural councils in both Victoria and New South Wales.

Then some time in the second half of 1944, W.S. Robinson, the influential leader of Collins House and managing director of the Zinc Corporation, organised a dinner party at the Melbourne home of another mining industry heavyweight, James Fitzgerald.

Young recounts that all the most powerful press owners and managers were present: Keith Murdoch, Rupert Henderson, (general manager of the Fairfax company), Frank Packer (owner of Consolidated Press) and Eric Kennedy (Associated Newspapers). Over dinner and drinks, Menzies sought and obtained their blessing to create a new political party. Thus the media were godparents to the Liberal Party.

So it’s hardly surprising that with rare exceptions, Australia’s newspapers have supported the election of Liberal-National coalition governments. Young produces a table showing the partisan support of major newspapers for every federal election between 1943 and 1972. It shows the conservative side of politics receiving 152 endorsements to Labor’s 14.

Naturally, this political support came with strings attached. These varied with the times and circumstances, but the most far-reaching concerned the newspaper companies’ determination to own whatever commercial radio licences they could get their hands on – and later, to repeat the exercise when television was introduced.

It was their success in both that gave rise to the book’s title, Media Monsters. They were no longer simply paper emperors, but omnipresent oligarchs of what is today called legacy media: newspapers, radio and television.

How they accomplished this feat, and the impact it continues to have on Australia’s democracy, is central to the story this book tells.

The major newspaper companies built these empires largely through interlocking and reciprocal share-ownership arrangements. These arrangements provided strong defences against takeovers. At the same time, they disguised the true control of radio and television stations from regulators concerned about Australia’s intensifying concentration of media ownership.

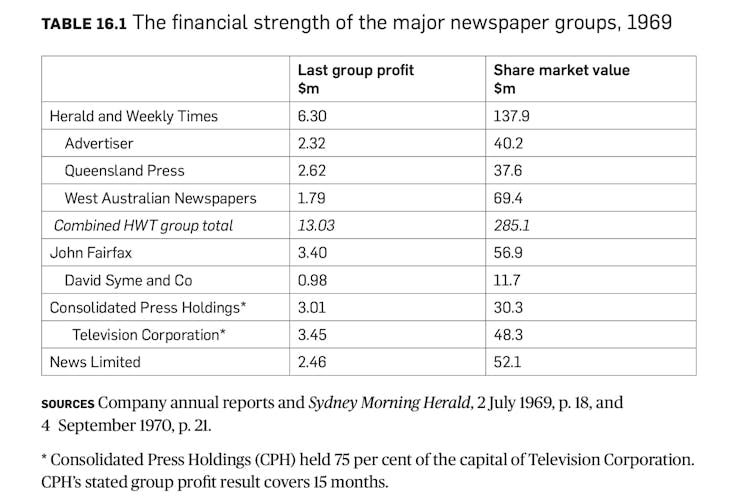

In another table, Young lists all the major interests and assets held by the five media monsters as they stood in 1969: HWT, Fairfax, David Syme and Co (in partnership with Fairfax), Consolidated Press (the Packer organisation) and News Limited (Rupert Murdoch).

To illustrate what these interlocking arrangements meant in practice, your reviewer – working as a journalist on Fairfax’s Sydney Morning Herald in 1969 – typed his copy on what was called 8-ply (the original and seven carbons).

The original and some of the carbons went to the Sydney Morning Herald. But carbons went also to the company’s Macquarie radio network, its Sydney television channel, ATN 7, to Australian Associated Press (AAP) and to what was called the interstate room.

From there, the copy was shared via telex with all the interstate papers with which the Sydney Morning Herald had reciprocal copy-sharing arrangements. At that time, this included all the HWT papers: the Sun News-Pictorial in Melbourne, the Courier-Mail in Brisbane, the Advertiser in Adelaide and the Mercury in Hobart. This concentrated power arose entirely from cross-ownership and reciprocal deals the public and policymakers had little grasp of.

Recognising this, in the dying days of his prime ministership, Menzies made a desultory attempt at placing some limits on any further concentration. But his agency for doing so, the Australian Broadcasting Control Board, was as timid and ineffectual as its successors – with the honourable exception of the Australian Broadcasting Authority and its associated tribunal.

Unfortunately, this was emasculated by the Hawke-Keating governments as part of their cosiness with big media in the 1980s. But for that story, we will have to await the hoped-for completion of Sally Young’s trilogy.

Journalism plays an important but narrow role in this history. It is there as a tool: as a means to an end, rather than as an end in itself. Instead, this is a story about an industry – about a reciprocating engine of money, power and influence. The journalism and the journalists who figure in it do so as servants of this machine.

Emblematic of this is Alan Reid, Frank Packer’s man in Canberra, who combined his journalism with lobbying for his boss – and who led the charge to bring down John Gorton and replace him with the hapless Billy McMahon, eventually swept from office by Gough Whitlam in 1972.

All through the book, the journalism of opinion is the focus: the editorials advocating for the advancement of this politician or that political party, along with the political reporting in support of these endeavours.

Young has an engaging style and leavens the story with humour, where opportunity offers. There is a picturesque sketch of Lieutenant-Colonel Edwin Hill Balfour Neill, chairman of the board of David Syme and Company when it owned The Age.

Young draws on various sources to present a caricature of this monocled Wodehousian buffer, with a carnation in his lapel and a fondness for polo and grouse-shooting. Asked by the then-leader of the federal opposition, Arthur Calwell, how circulation is going, Neill replies: “Excellent thank you. I always keep myself very fit.”

There is one irritant in this otherwise admirable work. Devices called “textboxes” keep popping up in the most unlooked-for places, interrupting the narrative with sidebars that are quite interesting in themselves, but distracting. In the next edition, they should be collected at the end of chapters.

It is a quibble. This is a work that deserves to stand among the giants of academic research and authorship on Australian media and political history.

Correction: the original version of this article reported that Alan Reid sought to bring down Billy McMahon; in fact, he sought to bring down John Gorton and replace him with Billy McMahon. The article has been amended to reflect this.![]()

Denis Muller, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Advancing Journalism, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.