- Have any questions?

- 02 7200 2179

- media@commsroom.co

- Have any questions?

- 02 7200 2179

- media@commsroom.co

When I look out into a class of journalism students, the faces I see will often belong to young women. In contemporary journalism education, this is the norm. In many countries, about two thirds of journalism tertiary students are female. And in Australia, women have held the majority of journalism jobs for some time.

This is a remarkable turnaround when you consider journalism was, not that long ago, almost entirely produced by men. It was only after the 1950s that women started joining the profession in small numbers. Even then, they were typically confined to writing for the “women’s pages”.

Before this time, female journalists were almost unheard of. Which makes the women of Bold Types, who worked as journalists in Australia from 1860 to the end of World War II, particularly worthy of our attention.

Review: Bold Types: How Australia’s First Women Journalists Blazed a Trail – Patricia Clarke (National Library of Australia Publishing)

Facing obstacles at every turn, they were adventurous and incredibly courageous. As author Dr Patricia Clarke writes:

The journalists in Bold Types were a particularly ground-breaking group, given the societies in which they were living. The earlier journalists wrote thousands of words in longhand using quill pens. They ventured into muddy battlefields, down mines and into slums and prisons in their crinoline-style, ankle length dresses. Women who reached positions of standing and power could suffer the full brunt of gender discrimination either publicly or subtly. They also had to ignore the ethos of a society that disapproved of middle-class women working at all, much less in a such a public job at journalism.

An historian and author, Clarke is well placed to tell these stories. She worked as a journalist in male-dominated newsrooms, including at the ABC, during the 1950s and 1960s. Gender inequality was part of the deal, she writes, and sexual harassment was rampant.

At the time, most female journalists were employed on the women’s pages, where they typically covered social events and were paid at low rates, despite their coverage generating significant revenue from advertisers.

Some of the women who feature in Bold Types wrote for the women’s pages, often in addition to more satisfying work. But others eagerly took on roles that were usually only assigned to men. These include Anna Blackwell, Australia’s first female correspondent, who reported from Paris for the Sydney Morning Herald from 1860, and Jessie Couvreur, who worked for the London Times as Brussels correspondent in the 1890s after growing up in Hobart.

State Library Victoria/Mathilde Philippson

Others demonstrated remarkable bravery and resilience in jobs that were physically demanding and dangerous. Flora Shaw, a British journalist, travelled throughout regional Australia in 1892. Travelling by buggy and steamer, Shaw reported on the sugar, mineral and pastoral industries of Queensland.

She then toured Western sheep stations in a journey of more than 800 kms in an open buggy, in temperatures often above 40 degrees. After a short stint in Brisbane, she continued her journey through the southern states, reporting on the fruit and butter industries in Victoria and on the Barossa wine region. The hazards and discomfort she experienced were recounted in letters to her sister.

J.J. Dwyer/State Library Western Australia 019926PD, CC BY

The trip took a toll on her health, but Shaw continued to write and post her articles to The Times. She returned to London in late 1883 to wide acclaim and was appointed to the influential position of Colonial Correspondent, a role that saw her become the highest-paid female journalist in London.

A few years later, another female journalist, Edith Dickenson, also travelled great distances under difficult circumstances to fulfil her reporting role. She was Australia’s first female war correspondent, sent to Durban in 1900 to cover the Second Boer War.

Edith had already lived an unconventional life, moving to Melbourne from England in 1886 to meet her lover, Dr Augustus Dickenson. Both Edith and Augustus were married to others; Augustus was eventually prosecuted and found guilty of deserting his infant daughter in England. For many years he regularly “disappeared”, moving between small towns in regional Australia, always accompanied by Edith and her sons.

During this time, Edith became a photographer and eventually began producing newspaper articles as a freelancer. Before being assigned to cover the war for the Adelaide Advertiser, she wrote about her journeys through India and the East, establishing herself as an “intrepid traveller with remarkable stamina”.

These traits were to prove invaluable in South Africa, where she was able to move across the country after receiving a formal correspondent’s pass. She gained a reputation for her detailed scene-setting and even-handed approach. When all civilians were barred from the town of Ladysmith due to high rates of dysentery and enteric (typhoid) fever, Edith managed to gain entry and interview survivors.

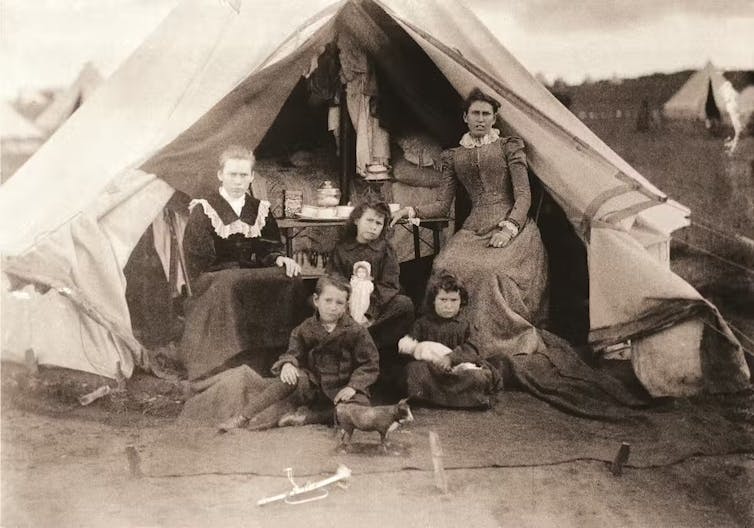

By October 1900, the British had taken the Boer capitals and most of the major fighting was over, so Edith left South Africa. However, she returned in 1901 to report on the concentration camps set up by the British to house displaced women and children.

Photographical Collection Anglo Boer War Museum Bloemfontein SA

“During the next six months, Edith’s Advertiser articles were a savage indictment of conditions in British camps,” Clarke writes.

Everywhere she reported overcrowded tents, some located nearly two kilometres from a source of water, others set up on marshy ground. Food was inadequate, unsuitable, and contaminated. Malnutrition and epidemic diseases were rife, and mothers were separated from their children.

Dickenson died at age 52 after completing a third trip to South Africa. According to Clarke, she remained unequalled for many years, including the two world wars, when the movements of Australian women journalists were tightly controlled.

Not all the stories in Bold Types are as dramatic as Shaw and Dickenson’s, but each of the women profiled were extraordinary for their times. Most were freelancers, relying on low and irregular payments. Many were also activists fighting for women’s and/or workers’ rights. Almost all who worked in mainstream media faced opposition and condescension from male colleagues who felt threatened by their presence.

Some, like Texas-born Jennie Scott Griffiths, worked as journalists while overseeing large families (Scott Griffiths had ten children). Others, such as feminist and social activist Alice Henry, defied convention and never married or had children. In many cases, they brought attention to the discrimination and exploitation experienced by women. Speaking out against the establishment rarely led to success. A sad and recurring theme throughout the book is that these women often died in obscurity.

The women of Bold Types led the way for the many prominent women reporters and presenters in Australia today. The opportunities in journalism for women have grown hugely since the late 1970s, which signalled the end of the traditional women’s pages.

However, we still have a long way to go, cautions Clarke, echoing the Guardian’s Amy Remeikis in her introduction to the book. “The public profile of notable women disguises the fact that women journalists struggle to attain real influence in decision-making roles,” Clarke says. “Few reach leadership positions with power over recruitment and promotion, and content is still determined predominantly by men, resulting in sexual bias.”

Bold Types provides a welcome and overdue rewriting of the history of Australian journalism. It should be of interest to reporters, news bosses and educators, who can finally acknowledge the pioneering contributions of our first female journalists.![]()

Kathryn Shine, Associate Professor, Journalism, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.