- Have any questions?

- 02 7200 2179

- media@commsroom.co

- Have any questions?

- 02 7200 2179

- media@commsroom.co

Adults might assume young people are not engaged in current affairs.

But our survey reveals most Australian children and teenagers have a significant interest in the news. There has, however, been a drop in interest from our 2020 survey, done at the start of COVID.

Our research also shows children and teenagers increasingly get news from social media, but many do not understand how algorithms select the news they see.

This suggests there needs to be more focus on teaching media literacy in schools.

In June, we asked 1,064 children and teens (aged eight to 16) from around Australia how they access and consume news media. This repeats earlier surveys we did in 2017 and 2020.

When asked about the news they accessed yesterday, most young people (83%) said they had received it from at least one source. One third (33%) used three or more sources.

There has been a drop in young people’s news engagement since the 2020 survey, which was conducted at the end of the Black Summer bushfires and the start of COVID. In 2020, 88% of young people had consumed news from at least one source and they were getting news more frequently from family, friends, teachers and television.

This decline mirrors a 2023 survey on Australian adults, which suggests people increase their news consumption during major national events.

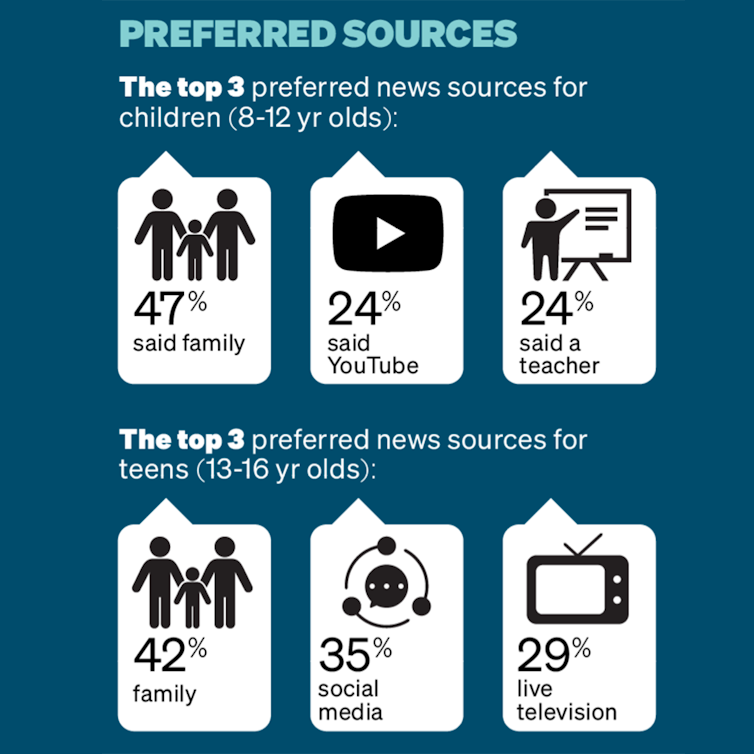

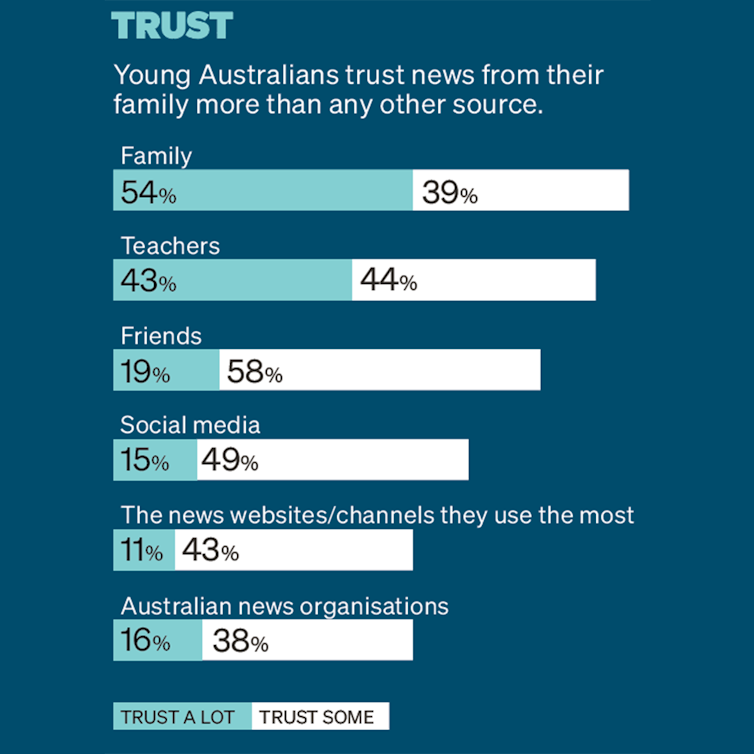

Family and friends were the top sources of news for young people, with survey respondents also reporting high levels of trust in these sources.

But social media is an increasingly important source of news, moving ahead of television for the first time for teenagers. Almost four in ten children (37%) and more than six in ten teens (63%) say they often or sometimes get news from social media. This compares to 39% of children and 41% of teens who often or sometimes get news from live TV.

Interestingly, when young people were asked about getting news on social media, only a small proportion (4-20% depending on the platform used) said they intentionally use social media to find or get news. Instead, they mostly report encountering news while they are using social media for other purposes.

When using social media to get news, half the children in our survey said they preferred YouTube, followed by TikTok (21%) and Facebook (13%). Teenagers preferred YouTube (31%), TikTok (24%) and Instagram (19%).

Given so many young people regularly get news on social media – and this increases sharply as they enter their teen years — it is surprising only 40% of young people aged 12-16 years are familiar with the term “algorithm” in relation to news.

Technology companies – such as Google and TikTok – use algorithms to select news based on what they think users will like. This can skew the news people consume.

Just over half (56%) of the group who had heard of the term algorithm in relation to news viewed algorithms as a helpful tool that enhances the relevance of news to them. However, only 27% of this group trusted algorithms to curate balanced and accurate news.

This suggests there is an important opportunity for parents, educators and news organisations to increase young people’s understanding of how algorithms are used to deliver news online.

The lack of awareness about the role algorithms play in delivering online news suggests children are not getting sufficient media literacy education in school.

Only one in four young people (24%) said they’d had a lesson at school in the past year to help them work out if news stories are true and can be trusted – and this is the same for children and teenagers.

Less than one third (29%) of respondents reported they had been taught how to create their own news story in the past year

We divided our respondents into five groups based on their level of engagement with news.

Young people with the highest level of engagement with news were four times more likely to report they often or sometimes ask critical questions about the news they consume than those with the lowest level of interest in news (76% versus 18%).

These critical questions include “how are different groups of people likely to respond to this news story?”, “how are people, places or ideas being presented in this news story?” and “what technologies were used to produce and share this news?”

Young people with a high level of engagement with news are also more likely to take actions that will help them to avoid misinformation. For example, they are six times more likely to report checking multiple sources to verify news when compared with young people with a low level of interest in news (63% versus 10%).

This suggests news engagement is linked to many positive outcomes that may help young people to avoid misinformation.

The shift in young people’s news engagement toward social media highlights the need for consistent media literacy education across Australia.

This can help young people learn more about social media business models, visual modes of communication (particularly video), methods for identifying misinformation, privacy settings and how algorithms work.

This kind of education will help young people to grow up being engaged but critical news consumers and citizens. ![]()

Tanya Notley, Associate Professor in Digital Media, Western Sydney University; Michael Dezuanni, Professor, Queensland University of Technology, and Sora Park, Professor of Communication, News & Media Research Centre, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.